October 14, 2009

Tone #4

Over at Chizumatic, Steven brings up my favorite non-F1, non-anime subject, namely the Battle of Midway. In his post, he tells the story of the Japanese scout planes at the battle, and how the Tone's #4 scout plane left an hour late because of a defective catapult. He then repeats the conventional thinking about the subject:

If Scout 4 had launched when the other scouts had, it would have radioed back much earlier. The second strike could have been launched -- towards Yorktown -- before the first strike returned from Midway... ...The failure of the Tone's catapult is one of the most fortuitous breaks in the history of war, with consequences far out of proportion to its apparent importance.

As it turns out, recent scholarship has turned this conventional wisdom on its ear. No less a source than the 102-volume official Japanese history of the War in the Pacific, the Senshi Sosho, calls this bit of history into serious question. Written in the '60s and '70s from official Army and Navy documents and personal diaries and records, it hasn't yet been translated into English (except for one volume, ;">Japanese Army Operations in the South Pacific Area: New Britain and Papua Campaigns, 1942–43, downloadable here), and may never be. It turns out that Military Japanese isn't the same as the regular language, and the number people who can read it are rather thin on the ground.

However, that doesn't mean that parts of it haven't been translated. Much of the volume on the Battle of Midway, for example, has become available to researchers. The authors of the great book Shattered Sword, Jon Parshall and Anthony Tully, drew heavily upon the information contained therein, and came to a rather surprising conclusion:

Tone #4 was actually one of the few pieces of GOOD luck the Japanese Navy had at the Battle of Midway.

It turns out that the pilot of Tone #4, Petty Officer Amari, for reasons lost to us now (neither he nor his crew survived the war) may very well have not flown the correct flightpath after he was launched an hour late.

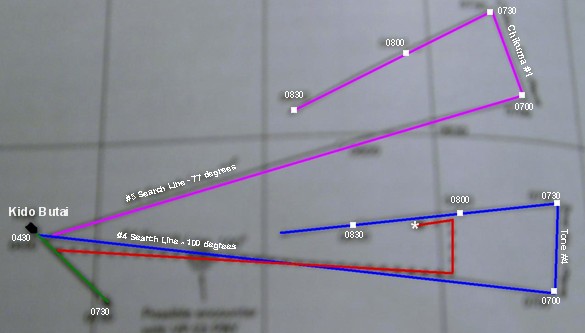

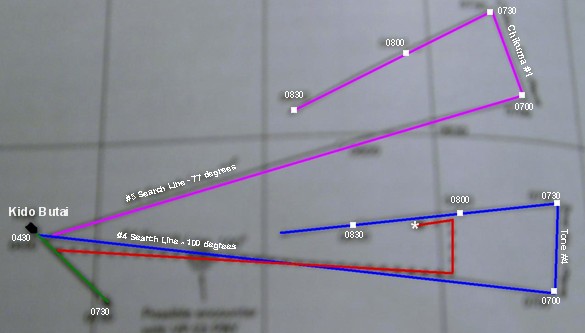

The blue line is the planned flight path for Tone #4. The red line, however, is the path that the Senshi Sosho believes it actually flew.

The reason for this possible flight path is quite simple: it would have been impossible for Tone #4 to have discovered the Yorktown and TF16 where it did and when it did (at 0740, the asterisk on the map) had it flown the correct route. Remember, it was launched at 0530, approximately, over an hour late. This would have put it at the end of it's outbound leg at 0800, instead of the scheduled 0700, and it would have turned for home at about 0830.

Make no mistake, Tone #4 would have discovered the Yorktown and TF16 had it flown the correct route... at about 0915, on the inbound leg of the search. Instead, because it appears that it flew a truncated course, it found the Americans over 90 minutes before it should have.

Had it flown the expected path, Tone #4's sighting would have come after the Hornet's torpedo squadron had made their fatal charge at Kido Butai (0920), and as the Enterprise's torpedo planes began their attack runs (0940), and just only 20 minutes before the hammer of the Dauntlesses came down.

However, nothing would have gotten the second strike at Midway Island off the Japanese carriers: the timeline of American attacks didn't give the second wave a chance to be lifted to the flight decks, spotted and launched (See my post "What If #3: Midway... Timing Is Everything" for a conversation about that point).

At least Tone #4 gave Admiral Nagumo 90 minutes to get his planes armed correctly if he got the time to get them in the air. That never happened.

Comments are disabled.

Post is locked.

If Scout 4 had launched when the other scouts had, it would have radioed back much earlier. The second strike could have been launched -- towards Yorktown -- before the first strike returned from Midway... ...The failure of the Tone's catapult is one of the most fortuitous breaks in the history of war, with consequences far out of proportion to its apparent importance.

As it turns out, recent scholarship has turned this conventional wisdom on its ear. No less a source than the 102-volume official Japanese history of the War in the Pacific, the Senshi Sosho, calls this bit of history into serious question. Written in the '60s and '70s from official Army and Navy documents and personal diaries and records, it hasn't yet been translated into English (except for one volume, ;">Japanese Army Operations in the South Pacific Area: New Britain and Papua Campaigns, 1942–43, downloadable here), and may never be. It turns out that Military Japanese isn't the same as the regular language, and the number people who can read it are rather thin on the ground.

However, that doesn't mean that parts of it haven't been translated. Much of the volume on the Battle of Midway, for example, has become available to researchers. The authors of the great book Shattered Sword, Jon Parshall and Anthony Tully, drew heavily upon the information contained therein, and came to a rather surprising conclusion:

Tone #4 was actually one of the few pieces of GOOD luck the Japanese Navy had at the Battle of Midway.

It turns out that the pilot of Tone #4, Petty Officer Amari, for reasons lost to us now (neither he nor his crew survived the war) may very well have not flown the correct flightpath after he was launched an hour late.

Map adapted from Shattered Sword.

The pink line is the flight path taken by Scout plane #1 from the cruiser Chikuma, which left at 0430 and flew the planned search pattern.The blue line is the planned flight path for Tone #4. The red line, however, is the path that the Senshi Sosho believes it actually flew.

The reason for this possible flight path is quite simple: it would have been impossible for Tone #4 to have discovered the Yorktown and TF16 where it did and when it did (at 0740, the asterisk on the map) had it flown the correct route. Remember, it was launched at 0530, approximately, over an hour late. This would have put it at the end of it's outbound leg at 0800, instead of the scheduled 0700, and it would have turned for home at about 0830.

Make no mistake, Tone #4 would have discovered the Yorktown and TF16 had it flown the correct route... at about 0915, on the inbound leg of the search. Instead, because it appears that it flew a truncated course, it found the Americans over 90 minutes before it should have.

Had it flown the expected path, Tone #4's sighting would have come after the Hornet's torpedo squadron had made their fatal charge at Kido Butai (0920), and as the Enterprise's torpedo planes began their attack runs (0940), and just only 20 minutes before the hammer of the Dauntlesses came down.

However, nothing would have gotten the second strike at Midway Island off the Japanese carriers: the timeline of American attacks didn't give the second wave a chance to be lifted to the flight decks, spotted and launched (See my post "What If #3: Midway... Timing Is Everything" for a conversation about that point).

At least Tone #4 gave Admiral Nagumo 90 minutes to get his planes armed correctly if he got the time to get them in the air. That never happened.

Posted by: Wonderduck at

10:37 PM

| Comments (4)

| Add Comment

Post contains 677 words, total size 5 kb.

1

From what I've read, I concur. The piecemeal nature of the attacks turned out to be the key feature, rather than a bug.

I'd normally highly recommend historyanimated.com, which does an excellent job of putting these events into a minute-by-minute perspective, but they seem to be down. Another pretty darn good site is SteelJaw Scribe's blog, which has put together some nice reporting on the naval battles in the Pacific.

I'd normally highly recommend historyanimated.com, which does an excellent job of putting these events into a minute-by-minute perspective, but they seem to be down. Another pretty darn good site is SteelJaw Scribe's blog, which has put together some nice reporting on the naval battles in the Pacific.

Posted by: Big D at October 15, 2009 10:53 AM (LjWr8)

2

Shattered Sword is pretty good, though some of the conclusions are suspect (The utility of Kaga if she had not been sunk at Midway, for example.).

I highly recommend it.

C.T.

Posted by: cxt217 at October 15, 2009 02:21 PM (PMYtm)

3

Hey Wonderduck! What always comes back to fascinate me is how easily it could have turned out disasterous for the U.S. Such a near-run battle...

I have to second Big D - Steeljaw Scribe has written quite a bit on Midway, and worth your time if you haven't seen it.

In addition, a collection of bloggers including SteelJaw and the U.S. Naval Institute are running a series on Guadalcanal and the Solomon Islands camapaign. Great stuff.

Steeljaw Scribe: http://steeljawscribe.com

Solomons Campaign blog: http://steeljawscribe.com/tag/solomon-islands-campaign-blog-project

I have to second Big D - Steeljaw Scribe has written quite a bit on Midway, and worth your time if you haven't seen it.

In addition, a collection of bloggers including SteelJaw and the U.S. Naval Institute are running a series on Guadalcanal and the Solomon Islands camapaign. Great stuff.

Steeljaw Scribe: http://steeljawscribe.com

Solomons Campaign blog: http://steeljawscribe.com/tag/solomon-islands-campaign-blog-project

Posted by: UtahMan at October 15, 2009 02:24 PM (p1tb6)

4

I was thinking about the aftermath of Midway in terms of what it did to the Japanese Naval Air after I ran into this article on Strategypage.com

http://www.strategypage.com/htmw/htlead/articles/20091016.aspx

"The situation was the same in the Pacific, where increasingly effective U.S. submarine attacks sank so many Japanese tankers that there was not enough fuel available to train pilots. In 1941, a Japanese pilot trainee 700 hours of flight time to qualify as a full fledged pilot in the Imperial Navy, while his American counterpart needed only 305 hours. About half of the active duty pilots in the U.S. Navy in late 1941 had between 300 and 600 hours flying experience, a quarter between 600 and 1000 hours, and the balance more than 1000 hours. Most of these flight hours had been acquired in the last few years. But at the beginning of the war nearly 75 percent of the U.S. Navy's pilots had fewer flying hours than did the least qualified of the Japanese Navy's pilots.

On the down side, the Japanese pilot training program was so rigorous that only about 100 men a year were being graduated, in a program that required 4-5 years. In 1940, it was proposed that the pilot training program be made shorter, less rigorous, and more productive, in order to build up the pool of available pilots to about 15,000. This was rejected. Japan believed it could not win a long war, and needed the best pilots possible in order to win a short one.

Naturally, once the war began, the Imperial Navy started losing pilots faster than they could be replaced. For example, the 29 pilots lost at Pearl Harbor represented more than a quarter of the annual crop. The battles of the next year led to the loss of hundreds of superb pilots. This finally forced the Japanese to reform their pilot training programs. Time to train a pilot, and hours in the air spiraled downward. By 1945 men were being certified fit for combat duty with less than four months training. In contrast, the U.S. Navy was actually increasing its flight time, while keeping pilot training programs to about 18 months. In 1943, the U.S. Navy increased flight hours for trainees to 500, while Japan cut its hours to 500. In 1944, the U.S. hours went up to 525, while Japan cut it to 275 hour. In 1945, a shortage of fuel had Japanese trainee pilots flying on 90 hours before entering combat. In the air, this produced lopsided American victories, with ten or more Japanese aircraft being lost for each U.S. one."

Posted by: toad at October 17, 2009 01:29 AM (izWk3)

32kb generated in CPU 0.0111, elapsed 0.0757 seconds.

47 queries taking 0.0677 seconds, 279 records returned.

Powered by Minx 1.1.6c-pink.

47 queries taking 0.0677 seconds, 279 records returned.

Powered by Minx 1.1.6c-pink.