October 06, 2011

At 7am on June 4th, 1942, the signal was flashed to the American aircraft carrier USS Hornet: "Begin launching aircraft." The plan to ambush the Japanese Kido Butai had worked perfectly so far. The Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu and Soryu were some 155 miles away, long range for the 59 planes of the Hornet's Air Group launched that day, but quite doable.

By noon, only 31 planes had landed at Midway or on the Hornet. All were SBD Dauntless dive bombers. None of the TBD Devastators of Torpedo 8 or the F4F Wildcats of Fighting 8 had landed aboard, and never would. None of the SBDs of Scouting 8 or Bombing 8 had even seen the Japanese carriers. One third of the striking power that the US Navy had so carefully positioned had been completely wasted.

What had happened during those five hours became one of the US Navy's deepest (but open) secrets, suspected but unproven for over 45 years. It cost the lives of 31 airmen. It should have torpedoed the careers of two men destined to become admirals. It was The Flight To Nowhere.

At the time of the Battle of Midway, the Hornet (CV-8) was the US Navy's newest carrier. The third and last of the Yorktown-class of carriers, she was commissioned on October 20, 1941. She spent the next five months working up in the waters around Norfolk VA, before setting sail for the Pacific in March of 1942. She then carried the B-25 Mitchell bombers that comprised the Doolittle Raid on Japan. Despite this mission, her crew and her Air Group were still green to the ways of combat. Unlike her sister ships the Yorktown and the Enterprise, the Hornet had not participated in the island raids of early 1942 which had "blooded" the Air Groups of the other two carriers. In essence, the ship was still a rookie, playing in the big leagues of carrier combat.

While the ship and her crew were still wet behind the ears,

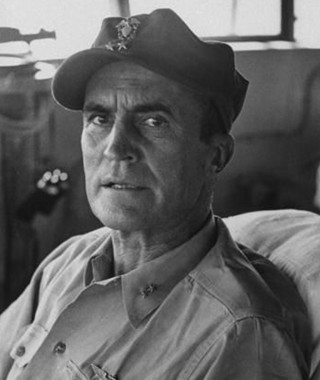

the same could not be said for the men in charge of the Hornet's fighting capabilities. Her commander was Captain (Admiral select) Marc Mitscher, who had more experience in the ways of naval air operations than practically any man in the US Navy. Unlike Admiral Halsey, who became a graduate of the 12-week Naval Aviator course at the age of 52, Mitscher had long known he was fascinated by flight. He became Naval Aviator number 33 in 1916, served as the XO of both the USS Langley (CV-1) and Saratoga (CV-3) and commanded NAS Anacostia. He made the first takeoff and the first landing on the Saratoga as well. After Midway, he'd become a legendary figure in the Navy, ending up as commander of Task Force 58 and a four-star admiral in charge of the entire Atlantic Fleet. In short, Captain Mitscher was not a man steeped in the traditions and doctrine of naval aviation, he helped create them.

the same could not be said for the men in charge of the Hornet's fighting capabilities. Her commander was Captain (Admiral select) Marc Mitscher, who had more experience in the ways of naval air operations than practically any man in the US Navy. Unlike Admiral Halsey, who became a graduate of the 12-week Naval Aviator course at the age of 52, Mitscher had long known he was fascinated by flight. He became Naval Aviator number 33 in 1916, served as the XO of both the USS Langley (CV-1) and Saratoga (CV-3) and commanded NAS Anacostia. He made the first takeoff and the first landing on the Saratoga as well. After Midway, he'd become a legendary figure in the Navy, ending up as commander of Task Force 58 and a four-star admiral in charge of the entire Atlantic Fleet. In short, Captain Mitscher was not a man steeped in the traditions and doctrine of naval aviation, he helped create them. Serving as Commander, Hornet Air Group (or CHAG) under Mitscher was CMDR Stanhope C Ring. Well liked by his superiors, those under his orders had something of a different view. Listed as Naval Aviator number 3342, Ring had served tours of duty on the Lexington (CV-2), Langley and Saratoga. He joined Fighting Squadron Five (VF-5) in 1927 flying the F6C Hawk. In 1928, VF-5 was moved to the Lexington to evaluate the effectiveness of dive bombing attacks against moving targets. These successful tests led directly to the formal adoption of dive bombing by the US Navy. Ring also served as naval aide to President Herbert Hoover and as the US Naval Observer on the HMS Ark Royal, Admiral Sir James Somerville in fleet command. Despite this impressive resume, Ring was not judged to be either a good pilot or navigator. On one training mission with his squadron, he reportedly got lost over the Gulf of Mexico and had to let the squadron XO guide the flight home. Reportedly he also commanded by authority as opposed to by example; he was the boss and you did what he said because he was the boss, not because he was respected. After the war, he was promoted to Rear Admiral.

Serving as Commander, Hornet Air Group (or CHAG) under Mitscher was CMDR Stanhope C Ring. Well liked by his superiors, those under his orders had something of a different view. Listed as Naval Aviator number 3342, Ring had served tours of duty on the Lexington (CV-2), Langley and Saratoga. He joined Fighting Squadron Five (VF-5) in 1927 flying the F6C Hawk. In 1928, VF-5 was moved to the Lexington to evaluate the effectiveness of dive bombing attacks against moving targets. These successful tests led directly to the formal adoption of dive bombing by the US Navy. Ring also served as naval aide to President Herbert Hoover and as the US Naval Observer on the HMS Ark Royal, Admiral Sir James Somerville in fleet command. Despite this impressive resume, Ring was not judged to be either a good pilot or navigator. On one training mission with his squadron, he reportedly got lost over the Gulf of Mexico and had to let the squadron XO guide the flight home. Reportedly he also commanded by authority as opposed to by example; he was the boss and you did what he said because he was the boss, not because he was respected. After the war, he was promoted to Rear Admiral.After the information from the scouts came in, the squadron commanders sat down to figure out the course the Air Group would fly. According to one source, CMDR Ring's course differed from those generated by the commanders of Scouting, Bombing and Torpedo 8 (Fighting 8's leader said he'd follow whatever was decided upon). Despite this, Ring overruled the others; they'd fly his course. At 7am on June 4th, 1942, after a short sprint to the west to close the range to Kido Butai, the Hornet was given the order to begin launching aircraft. The scouts out from Midway had the Japanese carriers at a location roughly bearing 239° from the Hornet's spot on the ocean. The plan of the day called for a "deferred departure." In effect, a deferred departure meant that the flight to the Japanese carriers would not begin until the entirety of the Hornet's Air Group was in the air and formed up. This technique promised to provide a strong balanced attack that was protected by fighters accompanying the flight. However, the deferred departure technique was found at the Battle of the Coral Sea by the crew of the Yorktown to be flawed; it tended to waste precious fuel, and therefore range. Further, it limited the entire strike group to the speed of the slowest squadron, that of the TBD torpedo bombers. Unfortunately, the Yorktown's air staff, owing to the late arrival of their ship at the Battle of Midway, never had the chance to communicate their discovery to their counterparts on the Enterprise and Hornet. What the Yorktown had found out was that it was best to launch the Devastators first and send them on the way to the target. Then would come the SBDs, and finally the escorting Wildcats. The Dauntlesses would catch up to the lumbering torpedo planes, and in short order the fighters would overhaul the dive bombers. No fuel wasted, and you still get the effect of the balanced attack.

As already mentioned however, this information wasn't known by the air staff of the Hornet. The trouble began with the command to begin launching the attack. First off the carrier were the planes of Fighting 8, which started climbing to an altitude of 20000 feet. The Wildcat was never a long-legged plane to begin with, but a climb to such heights had the effect of using up nearly a third of the fuel capacity of the F4Fs before the mission had even gotten rolling. Next came the SBDs of Scouting 8, carrying 500lb bombs, followed by Bombing 8, lugging 1000lb bombs. Last to come were six of the planes of Torpedo 8, all that could fit on a flight deck crowded by three other squadrons worth of planes. The remaining nine TBDs had to be brought up from the hangar deck and launched, all while the planes in the air circled, burning fuel. Almost an hour had passed by the time the last Devastator had gotten into the air, but at least the Air Group was heading to the attack.

Except they weren't, quite. CMDR Ring had decided that the two squadrons of SBDs would form up in parade formation for the flight out. This meant that his Dauntless would be the point of a gigantic V, with one squadron trailing behind on either side. While surely an impressive sight to behold, this rigid formation required much jiggling of the throttles to maintain position. This wasted even more gas. Meanwhile some 5000 feet above the dive bombers, the Wildcats of Fighting 8 cut lazy S-turns to keep from pulling away from the bombers... meaning that for every mile traveled, they may have actually been flying two. Even with their throttles set for best range, it's not hard to see that the fighters were going to be fuel critical fairly quickly.

Then came the biggest problem of the whole mission. As the Air Group left the Hornet behind, it became clear that CMDR Ring wasn't flying course 239°, which would put the strike force on the last known location of Kido Butai. Instead, it was flying roughly due west. While there is no way to know the exact course, many of the pilots interviewed long after the war essentially said that the course was 265°. This would take the Hornet's Air Group something like 100 miles due north of the Japanese fleet. For the first twenty minutes of the flight, nobody said anything.

At 816am, LCDR John Waldron, leader of Torpedo 8 broke radio silence and called to CMDR Ring. "You're going the wrong direction for the Japanese force," he said. An argument ensued between Ring and Waldron, which ended when the torpedo pilot said, in effect, "To hell with you." With that, Torpedo 8 banked off to the left. This was not just a minor disagreement, mind. Waldron was openly disobeying orders, defying his direct superior officer. A court martial could have been in his future, and his career was almost certainly ended by his actions, yet he was so sure that Ring's course was wrong he was willing to take these extreme steps. Taking a course that an hour later led them almost directly to the Kido Butai, Torpedo 8 became the only planes from the Hornet to encounter the Japanese that day. All of the Devastators of VT-8 were shot out of the sky, all but one man killed.

An hour later, or roughly the same time that VT-8 encountered the Japanese fleet, the escort fighters reached the point where they had to turn back to the Hornet or risk running out of gas on the way back. This was not an organized process; a fighter's fuel consumption was massively influenced by the pilot's skill at jiggling the throttle for just the right setting. The condition of an engine would also make a difference as to how much gas it used. The first two Wildcats turned back independently of the wishes of the VF-8's skipper, LCDR Mitchell. Eventually, all the fighters followed the lead of the first two though they took a separate flightpath. Perhaps confused by all the weaving and S-turns they had to make to keep position on the dive bomber squadrons, neither of the two groups of fighters took the right course to reach the Hornet, though they came close. Even using the tricky homing radio signal led to failure, though one or two of the junior pilots thought they saw smoke from the carrier at one point. All ten fighters wound up ditching in the ocean, coming down in five groups. Eight of the ten pilots were rescued after a few days in the water, though all were badly sunburned and dehydrated.

CMDR Ring and the two Dauntless squadrons plodded on for another half-hour or so, getting farther and farther from the Japanese fleet, until the fuel situation began to turn grim. With reality finally setting in that Waldron was correct, the SBDs of VB-8 and VS-8 began to wonder just what was going on... but as with everything else on this day, there was another problem. Scouting 8 had left the Hornet carrying 500lb bombs, but Bombing 8 was toting the larger 1000lb bombs, which Ring may have forgotten. Carelessly, the planes of VB-8 were in placed in a serious crisis. A quick look at fuel gauges made it clear that returning to the Hornet would be awfully marginal, so LCDR Johnson, squadron commander, made the call to head for Midway instead. Once again, Ring got on the radio and ordered one of the squadrons under his command to stay with him, and once again they were ignored. Bombing 8 went on their way. Most of them made it to Midway. Two planes had to ditch northwest of the atoll, and a third ran out of gas so close to the runway that it splashed down in the lagoon. Three others continued on and somehow made it home to the Hornet, though one can only imagine that they were running on fumes and clean living.

Then, after flying about 225 miles from the Hornet and low on fuel, Scouting 8's commander, Walter Rodee turned about to go home. The entirety of VS-8 followed him... except for Stanhope Ring. Suddenly, inexorably, his SBD was completely alone. Taking the hint, he too turned around. Unable to home in on the Hornet's homing signal, he climbed to 20000 feet and went via dead reckoning. For a wonder, he actually succeeded well enough to be the first plane of the attack force to land aboard. Standard Operating Procedure was that, after an attack, the first pilot to land was to immediately report to the carrier's Commanding Officer to tell him of the results. Instead, Stanhope Ring got out of his Dauntless, headed directly to his cabin and locked the door behind him. It wasn't until a few minutes later, when Rodee returned to the Hornet, that Captain Mitscher found out exactly what happened.

By noon, everybody that was going to land safely had done so. The Flight to Nowhere was over.

Click to enlarge.

The only After-Action Report filed was that for the Hornet as a whole, signed off on by Mitscher. Either none of the others actually wrote theirs, or they were suppressed. The Hornet's report was so incredibly whitewashed that Admiral Raymond Spruance, commander of Task Force 16, took the unprecedented step of writing in his own report that if there was any conflict between the reports from the Enterprise (CV-6) and the Hornet, the reader should take the Enterprise's report as definitive. Amongst other things, the report stated that the Air Group flew course 239° and when VT-8 broke away, it turned right, not left, to find the Japanese. It also put the ditching of VF-8 to the northwest of Midway atoll, as opposed to the northeast.

Everything that could have gone wrong for the Hornet's Air Group on June 4th, 1942, did. The escorting fighters gave no protection to the torpedo planes, got lost, ran out of fuel and ditched without ever firing their guns. The bombers never saw the enemy. The torpedo squadron was annihilated without scoring a hit. It was the sort of performance that could ruin careers. For a time, Mitscher believed his was completely over. Ring had lost all control over his Air Group entirely, and probably should have been lucky to ever get back to sea.

But the whitewashing of the entire incident began almost immediately. The Battle of Midway was, as Walter Lord put it, an "Incredible Victory." It was a time to celebrate, and the ugly truth was swept under the rug. Shortly after Midway, now-Admiral Mitscher was relieved of command of the Hornet and assigned a number of positions over the next year, before begin given command of Carrier Division 3 in early 1944. Stanhope Ring was awarded the Navy Cross for his actions on June 5th, 1942, during the attacks on the Japanese cruiser Mikuma. When Mitscher left the Hornet, Ring went with him as his Operations Officer. Both men probably should have seen their careers end at Midway. Instead, both moved up the ladders of command. Mitscher became a legendary commander, greatly admired by his pilots. Ring got his stars after the war.

The Battle of Midway was won on that day in June without the Hornet's Air Group showing up, what difference does it make? I believe it's quite possible that those dive bombers would have crippled or destroyed the Hiryu, the only carrier to survive the initial American attack. Of course, planes from the Hiryu's flight deck went on to (essentially) sink the USS Yorktown. So Mitscher and Ring's massive failure arguably cost the US Navy an aircraft carrier (and perhaps a second; see below), not to mention the lives of a number of pilots and aircrew.

The Hornet's career was sadly short. A little more than a year after she was commissioned, she suffered catastrophic damage in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, losing 140 of her crew. Attempts to scuttle her failed, and on October 27th, 1942, a burned out hulk, she was sunk by Japanese destroyers. She was the last American fleet carrier to be sunk in World War II.

During the Battle of Santa Cruz, she and the Enterprise faced off against three Japanese carriers and came off second best. The Enterprise was badly mauled and the Hornet lost. Would the presence of the Yorktown have made a difference? Would the tables have been turned? Is it possible that the Hornet might have even survived? We will never know obviously... it's certainly possible that the Yorktown would have been sunk at Santa Cruz as well after all... but it's not hard to imagine.

All because of a Flight to Nowhere.

Reference Works Used:

A Glorious Page In Our History - Robert Cressman, Pictorial History Publications (1990, 1996), ISBN 9780929521404

The Unknown Battle of Midway - Alvin Kernan, Yale Press (2005), ISBN 9780300122640

The First Team - John Lundstrom, Naval Institute Press (1984, 2005), ISBN 978159144717

No Right To Win - Ronald Russell, iUniverse Press (2006), ISBN 9780595405114

The Battle of Midway - Craig Symonds, Oxford University Press (2012), ISBN 9780195397932

The Last Flight of Ensign C Markland Kelly Junior, USNR - Bowen Weisheit, The Ensign C Markland Kelly Jr Memorial Foundation, Inc. (1993, 1996), ISBN not listed.

Posted by: Wonderduck at

11:00 PM

| Comments (19)

| Add Comment

Post contains 3052 words, total size 23 kb.

Posted by: Steven Den Beste at October 07, 2011 05:35 AM (+rSRq)

Out-bloody-standing, my friend. Now Ring is right down with "Swede" Larsen in the pantheon of screw-ups.

Nicely done and a smooth read. Gotta love it.

Posted by: The Old Man at October 07, 2011 10:05 AM (TcNy+)

Posted by: Wonderduck at October 07, 2011 11:12 AM (OS+Cr)

Posted by: David at October 07, 2011 11:48 AM (ttXyi)

It should be noted that Mitscher exerted a baneful influence on the planning of Hornet's air operations even before the battle was joined. He had a major say in the poor coordination between the escort fighters and the bombers which would have led to major disaster had the Hornet's birds attacked the Japanese carriers. And unlike Enterprise's George Murray, Mitscher did not redeem himself at all with his later actions through-out Midway for his earlier mistakes.

Even before Midway, the less than adequate performance of Air Group 8 had caused Bull Halsey to stand them down one day to conduct more training.

The performance of Hornet and Mitscher at Midway had ramfication for the latter during the war. Raymond Spruance's style of command depended on giving wide latitude to trusted subordinates, which meant less well regarded officers like Mitscher (When Spruance was CO of 5th Fleet, and Mitscher ran the Fast Carrier Force.) were kept on a tight reign. In Mitscher's case, that was probably a good move, since the man did not confine his mistakes to the decisions he made on Hornet. That includes the mishandling of his crucial decision to turn on the lights at Philippine Sea.

Then we have William Halsey's performance as fleet and theater commander, but that is another story.

Posted by: cxt217 at October 07, 2011 12:04 PM (ZGQLT)

Posted by: Siergen at October 07, 2011 05:09 PM (oK555)

Also, Bath and Body Works has pink sparkly light-up bath duckies. Goodness knows why, but they do. I will think of them as Twilight vampire ducks, in keeping with the Halloween items elsewhere in the store.

Posted by: Maureen at October 07, 2011 08:38 PM (VF957)

IIRC, Mitscher had already been tapped for a promotion to flag rank as well as a position in Washington by time Hornet sailed for Midway. Since the US won the battle, the Powers That Be probably decided that there was little gain from sacking people (However deserving some were.). And yes, his replacement as captain of the Hornet was aboard the carrier at Midway, but graciously delayed the change of command so not to create confusion and uncertainty on the eve of battle.

Posted by: cxt217 at October 07, 2011 09:29 PM (ZGQLT)

Posted by: Wonderduck at October 07, 2011 11:13 PM (o45Mg)

Posted by: cxt217 at October 07, 2011 11:19 PM (ZGQLT)

Excellent job in tying all the threads together on something as complex as the Midway battle. I, too, had read Walter Lord's book as well as several other accounts, but had never read as nice a summary of Hornet's AG fubar as yours. Bravo zulu, WD.

Posted by: jt at October 08, 2011 11:12 AM (NmSN+)

Posted by: Vaucanson's Duck at October 08, 2011 03:40 PM (OFJiW)

Now, as far as the official report of the Hornet is concerned, it would have been very difficult if not impossible for Mitscher to have written that Waldron had not only disobeyed orders to maintain strict radio silence but also disregarded Mitscher's and Ring's specific orders to follow Ring's Plan of Attack, and not court martialed the dead hero, Waldron. It would likewise have been difficult for Mitcher not to have court martialed at least two of the other three squadron commanders for also disregarding Ring's orders to continue with the original plan of attack.

Posted by: Jim Scanlon at October 30, 2011 10:57 AM (HoE4S)

Regarding your first point, VB-8 essentially followed that same flight profile. They never sighted Kido Butai, and never really came near it. Their nearest approach would have come around 1020 on the Weisheit map, approximately fifty miles. VF-8 would be down to about 20 minutes of fuel, the Dauntless crews would have to assume they would be swimming home. VT-8, carrying the torpedoes would, like as not, already be in the water. If that really was Mitscher and Ring's flight plan, it probably would have cost the Hornet her entire Air Group for even less effect than what it actually managed, instead of half of it.

Posted by: Wonderduck at October 30, 2011 01:19 PM (o45Mg)

Thank you. I have been looking for a clear article on this and you have done a great job. I was hoping to do something on this for my website, but now I don't need to!.

My take is we needed heroes. we got them, but not necessarily the right ones.

Best,

Jay Hambleton

Posted by: Jay Hambleton at December 10, 2011 11:20 AM (cbxDt)

Posted by: Wonderduck at December 22, 2011 09:43 PM (f/6aJ)

For example, the distance between the point were VF-8 claimed turned about 0910 and point were they ditched at 1040 (1.5 hours) is not less than 266 nautical miles even along the straight line! It means not less than 177 knots speed during fighters' return leg! Almost 50 knots more than F4F-4 cruising speed! It was only one example, but the timings, distances and speeds of other "tracks" are even more fantastic than VF-8's ones.

So you can believe in that revisionist Ñonspiracy rubbish as much as you want, but I recommend you to read discussions on The Battle of Midway Roundtable website, were the Midway veterans of VS-8 and VB-8 disproved Weisheit's fantasies.

Posted by: Midnike at February 19, 2012 01:46 PM (af8bp)

Posted by: Steven Den Beste at February 19, 2012 02:07 PM (+rSRq)

Arguing that the F4Fs of VF-8 didn't make it back to the Hornet, or weren't found to the northeast of Midway, or that the SBDs didn't leave Ring, or that Hornet's Air Group wasn't completely frittered away on a useless flight to nowhere, is ridiculous. I grant that it's quite possible that the tracks on the map aren't exact... and that there's no way to prove the matter either way. Given.

But Ring screwed up, from the beginning of the day to the end. Mitscher screwed up, from the beginning of the day to the end. What little after-action report was released from the Hornet was realized to be worthless, if not totally fictitious, by Nimitz.

That's the point of this post, Midnike, not exactly where VF-8 came down, or when VS-8 turned back to the Hornet. *shrug* I apologize if you didn't get that from the post. It'd be my fault if that wasn't clear enough.

Posted by: Wonderduck at February 19, 2012 02:26 PM (ZNgWw)

47 queries taking 0.4571 seconds, 295 records returned.

Powered by Minx 1.1.6c-pink.