December 01, 2011

In December of 1941, when the United States joined the rest of the world's industrialized nations in the first truly globe-spanning war, there was a tremendous range of single-seat fighters both in use and under design everywhere. However, to paraphrase a later persona, you go to war with the military you have, not the one you wish you had. What was a nation's front-line fighter plane in 1942 was obsolescent in 1943 and a death trap a year later. This entry will examine the best fighter planes from the "early years," and decide which of them is the best. Bear in mind, however, that in the hands of a talented pilot any one of these planes could beat any of the others. None of them could be considered a "dog," just perhaps not quite as good as the eventual winner.

As previously mentioned, the US gets two planes, one from the Navy

and one from the USAAF, since the two services had completely different

design criteria which generated completely different fighters. The

Japanese, Germans and British get one entry each.

The entries are presented in no particular order. Let's get on with it.

Messerschmitt Bf109E

When one thinks of planes of the Luftwaffe, either the Ju87 (best known as the Stuka) or the Bf109 is the aircraft that immediately leaps to mind. Rakish and shark-like, the 109 simply looks like a fighter... and it's the oldest design in this competition. The first 109s took to the air in 1937, becoming in effect the very first "modern" fighter plane. The 109E, or "Emil", was the first variant of the original design to use the 1085hp DB601A, an inverted V-12 inline engine. Armed with two 7.92mm machine guns mounted in the nose and one 20mm cannon in each wing, the 109 had decent firepower. One drawback to the mix of weaponry is that the wing cannon had different ballistic properties from the machine guns, making accuracy something of a challenge. Not a substantial one, however, as the 109 shot down more airplanes than any other German fighter. All of the major Luftwaffe aces flew the 109 at some time in their career, some flying nothing but. The Emil's top speed was around 345mph in level flight, and it could climb around 3000ft/minute. Range was around 500 miles. Maneuverability was acceptable, though not good at speeds over 290mph, when the unboosted controls could be heavy. Tricky to fly, the Emil required constant attention, particularly with a variable pitch propeller installed. One nice feature was fuel injection, which allowed a pilot the ability to nose over directly into a dive without the engine cutting out, a problem with engines that had carburetors. For the most part, the 109 was an attacking aircraft, best employed using "power" tactics. Pure dogfighting was to be avoided, replaced by high-speed attack runs, then swooping away to do it over again. The 109E was also to be the basis of the navalized Bf109T, to be used on the never-completed Graf Zeppelin aircraft carrier. Some 33000 Bf109s of all variants were built, and more aerial kills were scored with the fighter than any other aircraft in WWII.

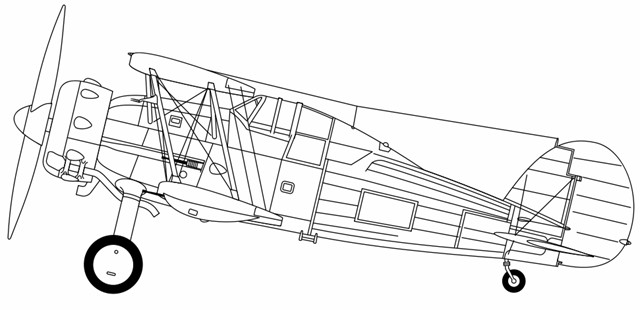

Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat

While not the first US Navy monoplane fighter (that honor goes to the Brewster Buffalo), the F4F is arguably the most famous American naval fighter ever. Originally designed as a biplane, it lost a flyoff against the Buffalo. At that point, Grumman took the plane back, chopped off the top wing, and suddenly a much better fighter was born. Powered by the 1200hp Twin Wasp 14-cylinder double-row radial engine, the plane weighed in at nearly 8000lbs. By comparison, the previously mentioned Bf109E weighed around 7000lbs. However, the F4F-4 needed to weigh a lot; carrier planes have to have a beefier structure because of the controlled crash that is a landing on an aircraft carrier. However, the F4F-4 weighed just under 1000lbs more than its predecessor, the F4F-3. Much of that extra weight came from the newly added wing-folding mechanism (which allowed four F4F-4s to be stored in the space of two F4F-3s) and the addition of two machine guns to the "dash-3"'s four .50cal. Somewhat surprisingly, the "dash-4" wasn't particularly popular with pilots that had flown the F4F-3. They said it was sluggish, and they had a point. Its top speed was 320mph, some 11mph slower than the earlier Wildcat. While the manufacturer said that it could climb at a rate of 2200ft per minute, in the real world pilots reported that they were lucky to reach perhaps half that. The Wildcat's main advantages lay in its beefy build. Heavily armored with self-sealing fuel tanks, it could take an enormous amount of damage and stay in the air. It could also shed appalling amounts of altitude in a dive, as one would expect from a plane said to be built by the "Grumman Ironworks." The six .50cal machine guns packed a terrific punch, and when flown defensively by experienced pilots, it could be a very dangerous opponent. The Wildcat's range was in the vicinity of 820 miles without external fuel tanks. It served with the US Navy, US Marine Corps and the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm (as the Martlet). Even though it was replaced by the F6F, the Wildcat never went out of service in WWII, flying off of small escort carriers (as the FM-1). Around 8000 Wildcats of all types were built between 1939 and 1944.

Curtiss P-40E Warhawk

Made famous by the American Volunteer Group (better known as the "Flying Tigers") in China, the P-40 was the primary US Army Air Forces fighter at the beginning of the war. It was powered by the only American-designed liquid-cooled engine used in WWII, the Allison V-1710, which generated 1150hp from its V12 configuration. It could pull the 8200lb fighter through the air at a robust 360mph, quite a good speed for the time. However, in a cost-cutting maneuver it was equipped with a single-stage/single-speed supercharger. Above 14000 feet, this limited the power the Allison engine could generate, leading to a steep dropoff in performance. Below 14000 feet, however, it was surprisingly nimble, particularly at high speed. It could even out-turn the Japanese Zero at speed. At lower speeds the P-40E wasn't nearly as maneuverable. However, one thing it could do extremely well is dive. It could accelerate into a dive in a way rarely seen before or since, and if the Wildcat could lose appalling amounts of altitude, the Warhawk fell like a brick with a propeller. Conversely, its ability to climb wasn't great; at full power, it could only do 2100ft per minute. Its range was 650 miles, but external drop tanks could extend that. The P-40E was considered well-armored, though it had the same weakness of all airplanes powered by liquid-cooled engines, in that a single bullet in the radiator could kill it. Pilots thought it easy to fly, with no particular vices in handling (though this is relative; any fighter could kill its pilot with a moment's inattention). P-40Es carried six .50cal machine guns, three in each wing; more than enough to deal lethal damage to any other fighter. The Warhawk was ruggedly simple, serving in just about every theater of operation in any weather condition you could name. From the frozen steppes of the Eastern front, to Africa, to the hideous conditions of the Pacific, you could find Warhawks. Nearly 14000 P-40s of all types were made, the third most amongst American planes.

Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero

There is no plane so closely identified with one nation than the Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero. The first naval fighter able to outperform its land-based cousins, it came as a distinct surprise when it appeared at the beginning of the Pacific war. Ridiculously lightweight (just over 5000lbs fully loaded) with a 14 cylinder Nakajima Sakae twin-row radial engine making 950hp, it could scoot along at 331mph. None of that tells the true story of the Zero, though. The A6M2 was far and away the most nimble fighter plane of WWII, bar none. It was a tremendous dogfighter, able to out-turn any opponent it faced throughout the entire war. It climbed like a scared cat as well, able to do 3100ft per minute. This performance was gained at a price, however, as it was built very lightly. It had no armor to speak of, and no self-sealing gas tanks. Hits that a Wildcat or Warhawk would shrug off would destroy a Zero. Being such a nimble airplane made it a difficult target, though, particularly in the hands of a skilled pilot. Its armament was a distinct weakness as well. While it was armed much like the Bf109E, with two 7.7mm machine guns in the engine cowling and one 20mm cannon in each wing, the two types of weapons could not have more dissimilar ballistic properties. The 20mm cannon was a slow-firing, low-velocity weapon, where the machine guns fired a high-velocity round. As such, the two types of rounds required the plane to be aimed in two places at once, save for close range, making it difficult to bring maximum firepower to bear. Perhaps the Zero's greatest strength lay not in its agility, but its range. It could fly over 1900 miles on a full load of fuel, which over the vast Pacific ocean was a terrific advantage. Almost 11000 Zeroes of various types were built over the entire time of the war, more than any other Japanese aircraft. As the war continued, it was eventually outclassed, but during the first years of the conflict it was incredibly deadly.

Supermarine Spitfire MkI

Serving with the RAF from the beginning of WWII into the 1950s, the Spitfire is without a doubt the iconic British fighter. It's arguably the most beautiful airplane ever made as well. However, it became an icon due to its abilities, not because of its looks. The MkI made its debut in 1938 behind the Rolls-Royce Merlin III inline V12 engine, producing 1030hp. This gave a top speed in the vicinity of 355mph with a climb rate of around 2900ft per minute. It could out-turn its main opponent, the Bf109E fairly handily. Weighing in around 6500lbs, it was an all-around strong airframe though with the weakness inherent of a liquid-cooled engine. It was designed as to protect the homeland, with a range of around 550miles. The aerodynamically elegant elliptical wing provided great lift with very little drag. However, this came at a cost as well. The Spitfire carried eight .303cal machine guns, four in each wing. Because of the thinness of the wing, these guns had to be widely spaced to give each one room. It was difficult to get them all converging at close range, with Supermarine suggesting 400yards as optimal. This robbed the already weak rifle-caliber bullet of a significant amount of hitting strength. However, they did put a lot of lead in the air, meaning some damage was almost guaranteed when firing at an opponent. One big disadvantage the Spitfire had was that the Merlin III had a carburetor. Pushing it straight into a dive, or staying inverted for any length of time, would cause the engine to cut out, a major handicap. Despite this, the Spitfire was an awesome piece of kit, one that could hold its own against any opponent at any time. Over 20000 of all marques were built, being steadily updated as time went on. There was even a navalized version, the Seafire, which proved to be perhaps the only failure the airframe experienced; the stalky landing gear proved to be too weak for carrier landings.

So there you have it: five contenders for the title of "Best Early Fighter." So which was best?

Right away, we can eliminate the F4F-4 and P-40E. While both were decent enough, neither was particularly outstanding. The Wildcat's main advantage was the ability to absorb damage, which is not what you want your fighter to be known for. The Warhawk was serviceable but outmatched against front-line aircraft; it was easy to make, easy to repair, and inexpensive to purchase. It was there, and it was better than not having a fighter at all. Next to fall, I believe, would be the Bf109E. While a good performer, both the Zero and the Spitfire have major advantages over it; both can out-turn and out-climb it, and the Spitfire was marginally faster.

This leaves us with a fight between the A6M2 and the Spitfire MkI. Historically, the more advanced MkV Spit faced off in the Pacific against the Zero and initially had its lunch handed to it. The British pilots were used to dogfighting their opponents, and took heavy losses before they learned that you couldn't dogfight a Zero. Even when they adopted "hit and run" tactics, they weren't quite able to bring the A6M2 to heel. The short range of the Spitfire, a feature in its original design, became a bug in the Pacific.

While the Spitfire's statistics would quickly outpace the Zero as newer versions with more powerful engines and weapons came online, this wouldn't occur until the "Late" time period. Which leads me to the inescapable conclusion that the Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero was the best Early-period fighter.

(I'm sure some readers are wondering why I didn't choose the P-38 Lightning instead of the P-40 Warhawk for the USAAF plane. While it's true the Lightning entered service during the Early time period, it didn't see significant combat until towards the end of my arbitrary date range for the period. If I was doing a "middle" period, it'd certainly be the choice for the USAAF. Consider it "bloggers prerogative". In other words, it's my call. So there.)

Coming soon: Which Fighter Is Best? Part III: The Late Years.

Posted by: Wonderduck at

11:21 PM

| Comments (19)

| Add Comment

Post contains 2298 words, total size 16 kb.

The biggest reason the P-40 did so well early in the war was because its pilots were very well trained and knew the plane. A squadron of P-40's fought out of Henderson Field for a while, and did very well against the Zero even though the Zero really was a much better plane.

I agree that the Zero was the best fighter of the early war.

Posted by: Steven Den Beste at December 01, 2011 11:39 PM (+rSRq)

Posted by: The Old Man at December 02, 2011 06:10 AM (TcNy+)

I'd have to argue on throwing out the BF109 so early, just based on the results it achieved. I'd put it into the top three with the Spitfire and Zero.

Posted by: David at December 02, 2011 10:30 AM (+yn5x)

David, that would actually be the squadron markings, not the type number, though technically it's incomplete. The correct number would be X-Y-Z, where X is the Air Group Number, Y the plane type (Fighter, Bomber, Scout, Torpedo), and Z the plane number in the squadron. So in 1942, 6-F-12 would be the 12th plane of the fighter squadron of the USS Enterprise's air group.

Posted by: Wonderduck at December 02, 2011 11:20 AM (OS+Cr)

There were no P-40s serving at Henderson Field during the Battle for Guadalcanal. They had the P-400, which was a bastardized export version of the P-39. Almost completely unsuitable for air combat (All the more so because they had no ground equipment to keep their oxygen system charged.), but its heavy armament and payload made it invaluable for ground support. The pilots there learned the hard way to leave tackling the Japanese aircraft to the F4Fs.

The A6M was very maneuverable but at high speeds or high attitudes, that maneuverability almost completely disappeared to the point of the aircraft being uncontrollable. That was why Japanese pilots were reluctant to go into steep dives in the Zero.

Finally, it is easy to overemphasize the importance of maneuverability in a fighter. Pilot skill and tactics often were far more determinative of the fighter's performance - which aircraft had greater maneuverability was only critical for the few pilots pushing the edge of the performance envelope.

Posted by: cxt217 at December 02, 2011 04:29 PM (Zye/c)

The genius of the Thach Weave was that it pretty much eliminated the value of maneuverability, and instead emphasized weapons and armor, in which areas the F4F (and pretty much all later American fighters) vastly outrated the Zero.

Also, this is from Fire in the Sky:

In April 1943 No. 15 Squadron (RNZAF) arrived on Guadalcanal with P-40s. RNZAF fighter squadrons took part in many of the fierce engagements triggered by each new U.S. Landing farther up the Solomons. These engagements did much more than the Guadalcanal campaign to damage the JNAF, and by the time the JNAF abandoned Rabaul in April, New Zealand fighters had claimed ninety-nine kills

Posted by: Steven Den Beste at December 02, 2011 05:02 PM (+rSRq)

http://wio.ru/aces/rechkalov.htm

Every star on that cowling is a downed German aircraft (quite a few were 109s).

Posted by: Author at December 02, 2011 08:41 PM (G2mwb)

I do remember that the American Volunteer Group ('Flying Tigers') were taught to climb high and dive towards the Japanese planes they fought. At least, that was mentioned in the book I read, way back in high school.

Chennault (leader of the AVG) was big on using that advantage of the P-40.

About the Spitfire, Bf109, and A6M2: the mix of guns with different convergence zones is surprising. Did the pilots have the ability to select which set to fire? Or did they have to fire both at once, and hit with whichever one was aimed right?

Posted by: karrde at December 03, 2011 08:04 AM (+Zz5p)

Posted by: Wonderduck at December 03, 2011 09:04 AM (2YMZG)

Erich Hartmann said that he preferred minimum range shots.

Posted by: Author at December 03, 2011 02:35 PM (G2mwb)

As far as the Zeke, it had a really poor roll rate, especially before the reduction in wing size with the Model 32. It's a remarkable technological achievement, but I'd take the Emil every day of the week and twice on Sunday, so long as operational radius wasn't my primary consideration.

And the Emil is clearly better looking than that effete Spitfire.

8-)

Posted by: Doug Sundseth at December 03, 2011 02:36 PM (xdhJI)

I'll point out again that any of these planes could shoot down any other in the contest. We're talking tiny percentage points differences between the top three.

Some time ago, I mentioned that I had a "What If...?" post I had to let go because I didn't know enough of the history involved. The basis of that post was "What If... the Germans had replaced their 109s with Zeros at the Battle of Britain?" I suspected the difference would have been huge, but I couldn't (and still can't) track down all the various permutations that change would cause.

Posted by: Wonderduck at December 03, 2011 04:03 PM (2YMZG)

"I had survived this mission simply because the Spitfire could sustain a continuous rate of turn inside the BF 109E without stalling - the latter was known for flicking into a vicious stall spin without prior warning if pulled too tightly. The Spitfire would give a shudder to signal it was close to the edge, so as soon as you felt the shake you eased off the stick pressure."

A good pilot could fly the 109 right on that edge, while an average pilot had to fly a few percent below that performance. With a Spit, even a relatively average pilot could hang on the performance edge. When combined with the 109s flying at the end of their endurance over England and the Spits flying over their own fields, the result was the performance differential that's usually reported.

"I'll point out again that any of these planes could shoot down any other in the contest. We're talking tiny percentage points differences between the top three."

Oh, clearly. To a large extent, the aircraft of the major combatants were direct responses to the challenges they faced during the war. The Japanese and Americans prioritized operational radius, the Japanese by sacrificing defense and the Americans by sacrificing maneuverability. American aircraft started significantly behind those of the Japanese and the Europeans, largely because of political concerns. The Germans and British sacrificed range for maneuverability or firepower.

The primary reason I'd choose a 109 over a Zero is that with good tactics, P-38s, P-40s, and F4Fs eventually attained something like loss parity with the Zero. And US experience in North Africa indicates that none of those aircraft could match the 109.

I'm treating this comment section in much the way I would treat the grognard discussion you alluded to in the first post in this series. And it wouldn't be that kind of discussion without disagreements opaque to anyone not in the in-group.

FWIW, when this is done, I'm willing to put forward the case that the Sherman is the most under-rated tank in WWII, (and arguably the best tank in WWII) as well**. 8-)

* An excellent data source, BTW, that I've not seen before.

** Seriously, not facetiously, but not based on which tank would win a tank duel.

Posted by: Doug Sundseth at December 03, 2011 10:14 PM (xdhJI)

Posted by: Steven Den Beste at December 03, 2011 11:24 PM (+rSRq)

Posted by: brickmuppet at December 03, 2011 11:42 PM (EJaOX)

I don't really know enough about fighters to have any strong opinions about them, except to follow the simple rule: the point of fighters isn't to dogfight, it's to assert and defend air supremacy over a theatre. That can be highly dependent on local conditions - logistics considerations, range, fuel efficiency, anti-aircraft artillery deployment, etc. What was the relative maintenance profiles of these aircraft, for instance?

Posted by: Mitch H. at December 04, 2011 08:20 AM (pvALX)

Even within the IJN in the discussions which led to the development of the Zero, there were experienced pilots who believed the emphasis on maneuverability to the detriment of other traits in a fighter design was a bad idea, and that inadequate maneuverability in a fighter could always be compensated for by improved pilot skill. Ultimately, those pilots were proven correct.

It is worth noting that most pilots did not push their aircraft to the limit. In that sense, arguments over the whether one fighter was more maneuverable tend to lead into a blind alley.

And as Len Deighton once noted, a common trait of all the highest-scoring aces like Hartmann was a willingness to get really close before opening fire on their targets. That fact led to one of the few peeves pilots had with the Spitfire - the mounts for the machine guns were simply too narrow to converge the fire of all the machine guns as close as the pilots wanted.

Posted by: cxt217 at December 04, 2011 06:05 PM (Zye/c)

Posted by: Author at December 04, 2011 11:29 PM (G2mwb)

http://player.vimeo.com/video/37599899

Posted by: David at March 13, 2012 03:41 PM (+yn5x)

47 queries taking 0.2888 seconds, 295 records returned.

Powered by Minx 1.1.6c-pink.