August 07, 2011

And then there was the Imperial Japanese military in World War II. The Army and the Navy didn't cordially dislike each other, they flat out hated each other. Each had their own plans on how to conduct the war and only deviated from them when they needed something from the other. The only reason you couldn't say that, say, the IJN's main enemy was the IJA was that the two services didn't openly shoot at each other. This open distaste extended to the designs of each forces' aircraft. While the US Army Air Forces and the US Navy designed planes that were radically different, that's because each service had different requirements. Strangely, the requirements for the IJN and the IJA were pretty much identical, save for the need for Navy planes to land on a carrier.

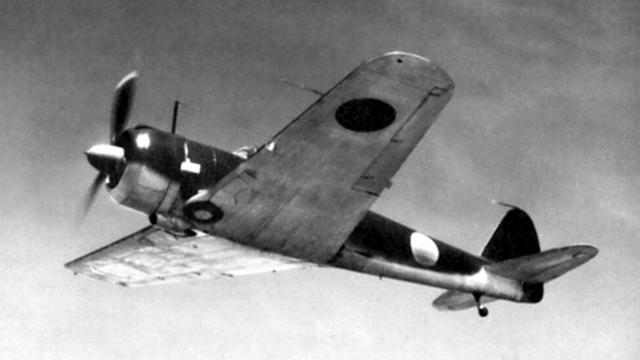

Both the Navy and the Army needed replacements for their front-line fighers, the A5M (Claude) and the Ki-27 (Nate), two very similar designs. Mitsubishi won the design contract for the Navy with the A6M, the famous Zero. Nakajima's design for the replacement of their own Ki-27 was the Ki-43 Hayabusa.

To say that there was a resemblance to the Zero would be something of an understatement. Both fighters used the same Sakae radial engine, at least to begin with. Both were slim, with slightly bent cantilevered wings. However, the Zero was nearly 700lbs heavier at all-up weight. This made the Hayabusa (Allied code name "Oscar") even more maneuverable than the already outstandingly nimble Zero.

Unlike the Zero, which passed its initial flight tests with ease, the Hayabusa was something of a dog right off the drawing table. In fact, the plane was nearly rejected on the grounds of being rather UNmaneuverable. Over the course of ten preproduction aircraft, the Oscar was modified with a larger wing, had its weight cut, and finally had a set of butterfly (or "combat") flaps installed. This proved to be the fix the fighter needed, and it was ordered into mass production.

One can safely assume that the main weight difference between the Zero and the Hayabusa was that the latter did not need the sort of structural strength a plane requires to land on an aircraft carrier. One drawback of this was that the Zero, which was never what one would call a sturdy aircraft, was by comparison to the Hayabusa carved out of a single block of iron. Another way the Hayabusa saved weight was in the form of weaponry. For most of the war, the Ki-43 carried only a pair of 7.7mm machine guns, the exact same armament as a Sopwith Camel from World War I.

At the beginning of the Pacific War though, this was enough. In combat, the Hayabusa was nearly as successful as the Zero. Being able to outturn and outclimb anything in the skies, once an Oscar got on a plane's tail, it could pretty much stay there at will. It was only a tiny bit slower than a Zero as well. All of this meant that it was a dangerous package. It even had some armor for the pilot and rudimentary self-sealing fuel tanks to boot.

The Hayabusa's main weakness was that it was ridiculously fragile. While less prone to catching fire like the Zero, it tended to come apart under Allied gunfire. Indeed, hits that even a Zero could shrug off were often enough to cause the Ki-43 to shatter like porcelain. The hard part was landing a blow on the nimble little plane in the first place.

Upgrades were applied to the Ki-43 over the course of the war. First, a larger engine was installed that gave better performance at high altitudes, then the guns were upgraded to 12.7mm. However, these upgrades were never going to be enough to keep up with newer Allied planes like the Hellcat, Corsair or Seafire. Replaced by the Ki-44 (Tojo) and Ki-61 (Tony), it was never entirely phased out and stayed in front-line service for the entire war. As with most other Japanese planes, it ended the war in a Kamikaze role, but not until nearly 6000 were built, making it the second-most popular Japanese fighter... behind only the Zero. Every IJA ace got the majority of his kills in the Oscar, and one source in my collection even claims that the Ki-43 was responsible for shooting down more Allied planes than the Zero. Not a bad record for a fragile, slow, undergunned fighter that was overshadowed by the A6M.

Today, only six Ki-43s are known to exist, and only one of those is in flyable condition.

Posted by: Wonderduck at

09:39 PM

| Comments (2)

| Add Comment

Post contains 853 words, total size 5 kb.

Aircraft design in that era always begins with the engine. The entire rest of the plane is designed around the shape, and more importantly the power output, provided by the engines.

Japanese aircraft engines were pitifully unpowerful. The Zero's engine only produced 950 horsepower. The Double Wasp (used in the F4U and F6F) produced 2000 HP when initially produced, and by the end of the war it was producing 2800 HP.

Some of that was the fuel: American avgas was 120 octane IIRC. But making it that rich means the yield per barrel of crude isn't very good, and petroleum was always scarce in Japan, so their fuel was terrible by comparison. But even if they'd been using American fuel, their engines were dreadful by comparison.

If the Japanese had tried to build their airframes the way the Americans did, with lots of strength and redundancy and armor all over the place, their engines wouldn't have been strong enough to get them into the air.

That's also why their fighters were relatively lightly armed. Guns and ammunition are heavy, and their planes couldn't carry as much as ours did.

All of which is why the Thach Weave was an effective tactic for the Americans all through the war.

Posted by: Steven Den Beste at August 07, 2011 10:09 PM (+rSRq)

It should be noted that within the IJN, the fighter pilots generally preferred features in the fighter design that became the A6M that was more a nimble, maneuverable dogfighter than than a fast, long range escort. The limitations of available power plants was major factor any Japanese design before and during the Pacific War, and the A6M tried to combined, with varying success, features of the two types of fighters. But its seems the majority of pre-war IJN pilots, even if they had a choice between the two types, would opt for the superior dogfighter despite the design limitations.

The ironic part is that IJN advocates of the heavier escort fighter argued that superior skill and tactics could compensate for flying less maneuverable aircraft against better dogfighers. They were ultimately proven correct, much to Japan's cost.

Posted by: cxt217 at August 08, 2011 03:12 PM (mnl77)

47 queries taking 0.3799 seconds, 278 records returned.

Powered by Minx 1.1.6c-pink.