May 19, 2011

While it's hard to imagine a submarine allowing itself to be caught on the surface these days, things were different in 1915. At the time, submarines were what would be called "submersibles" today: able to descend under the waves for a short time only, while doing most of their movement on the surface. Because their underwater time was limited, a sub would "go under" only when preparing for an attack run... and not always then. The torpedoes of the time were cranky, ill-tempered beasts that were often unreliable, and always in short supply. It was quite common for a submarine to sneak up on a target, surface, then engage with a deck gun. Of course this would only work against an unarmed freighter or transport; it goes without saying that an actual warship would receive a torpedo fired from underwater.

However, even this limited method of attack was extremely effective against unarmed merchant craft... so effective that England was on the verge of starving. The obvious defense, convoying, or putting a large number of merchant vessels in one group while defending them with one or more warships, was ruled out by the ship-strapped Royal Navy. There just weren't enough warships to go around. Something had to be done, and quickly. Two innovations arose from this desperate need.

The first was the armed merchantman. More of a throwback than a true innovation, at its heart the armed merchantman was a descendant of the age of sail, when almost every East Indiaman had a good number of cannon lining its rails to fight off pirates and privateers. The generic armed merchantman of WWI-vintage would have the firepower of a destroyer or light cruiser, six 6" guns and various numbers of smaller guns as a secondary battery. Since they were built as merchant vessels, they were however fragile: little in the way of compartmentalization to prevent flooding, little if any armor (other than raw size) to prevent damage, with a slow top speed that prevented running away. Armed merchantmen were mostly for use against commerce raiders as a self-defense measure: if a warship came upon an armed merchantman, at least there was some way to fight back. However, with their guns carried on deck, they were just as likely as a battleship to attract a torpedo from a submarine.

The second innovation was the Q-ship. Take a freighter and turn it into an armed merchantman... then hide the guns inside false panels or deck structures or belowdeck. When a submarine approached, it'd see a nice big fat undefended target, surface and engage with the deck gun... at which point, the Q-boat would drop the false panels, run out the guns and with the element of surprise blow the submarine out of the water. To be sure, they could take on a surface vessel as well, but their weapons were more designed to engage fragile submarines: a hole or two would prevent a sub from diving, trapping it on the surface. Q-ships had no set armament loadout, but multiple 3" guns were common.

Despite the clever idea, Q-ships were generally ineffective against submarines in WWI, accounting for less than 10% of all kills scored. Instead, they were more of a psychological weapon, preying upon the mind of a U-boat captain. If any freighter could be heavily armed and just waiting for you to surface, the sub captain might be more reluctant to do so, and either let the freighter go or waste a precious torpedo on it.

During WWII, there was a repeat of the WWI Battle of the Atlantic, and the Q-ship concept was revived. It was even less successful than in WWI, mainly because advances in submarine technology meant that a sub could spend less time on the surface, torpedoes were much less prone to failure and in greater supply. The Royal Navy commissioned nine Q-ships in 1939, two of which were sunk on their first mission. None of them sank a U-boat, and they were quietly retired in 1941. The US Navy converted five cargo vessels to Q-ships, one of which was sunk and the other four failed to engage a submarine during their two-year run.

And then there was the USS Anacapa.

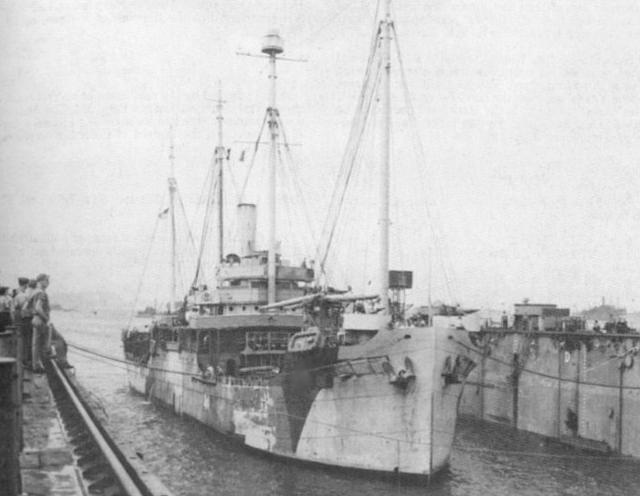

Originally commissioned as the SS Castle Town, renamed the Lumbertown, then renamed again to the Coos Bay, she was primarily a lumber ship. Taken into US Navy service in 1942, she carried two 4" guns and a depth charge projector on her main deck, all of which were camouflaged by false crates. She also had two 3" guns hidden behind hatches in her bow, and five 20mm cannon. Like other Q-ships, her job was to lure submarines to the surface, then blow them sky-high. Where the Anacapa was unique, however, was her area of operation: the Pacific ocean.

Shortly after rescuing the crew of the tanker, she was removed from her role as a Q-ship and converted to an armed transport. Her shallow draft and and flat bottom, originally designed to allow her to sail far upriver in Oregon and Washington to take on lumber, made her a rough ride in the Pacific Ocean, made her particularly well-suited for the island-hopping campaign against the Japanese. She was able to get much closer to shore to unload, particularly at places with poor or no harbors. Indeed, she was often the first ship in to resupply Marines after a landing. By the end of the war, she had delivered supplies at Tarawa, Saipan, Guam, Ulithi, Adak and Attu, as well as many other locations.

Returned to the lumber business after the Japanese surrender, she continued to perform that job until 1964, when she sank in the Columbia River on January 30th.

Posted by: Wonderduck at

10:09 PM

| Comments (7)

| Add Comment

Post contains 1167 words, total size 8 kb.

Posted by: Steven Den Beste at May 20, 2011 12:04 AM (+rSRq)

Posted by: Wonderduck at May 20, 2011 12:08 AM (n0k6M)

4 is a lot for such a small ship but I imagine that far upriver in the forest one might have to load very quickly to beat the tide. I imagine they stood her in good stead as an attack transport.

Posted by: Brickmuppet at May 20, 2011 08:36 AM (EJaOX)

...that far upriver in the forest...

The navigable rivers around here don't come anywhere near the areas where logging takes place. Logging happens up in the mountains, and though there are streams and rivers there, they're fast moving and shallow, with lots of rapids and waterfalls.

I figure that this ship was probably carrying lumber from somewhere like The Dalles down to Portland, carrying logs which had come to The Dalles by truck.

Posted by: Steven Den Beste at May 20, 2011 04:20 PM (+rSRq)

Seriously; I have no idea. I know nothing about the PacNW except for what I've seen with my own eyes (the Seattle area; I was a tourist for a week).

Posted by: Wonderduck at May 20, 2011 04:31 PM (n0k6M)

Yeah, it's pretty much always been that way. For one thing, a hundred years ago the river system was a lot less navigable. Before 1957 navigation of the Columbia stopped at Celilo Falls, which was flooded when the Dalles Dam was built.

There were ships above that point, but any cargo had to tranship by land to get around that waterfall because locks hadn't been built. (They were built as part of the Dalles Dam project.)

But it wouldn't have been useful for lumber purposes even so. East of there it's arid. Few trees, lots of grass, lots of sagebrush and rattlesnakes. Eastern Oregon and eastern Washington are the northern end of the Great Western Desert.

There's lots of trees in the Willamette Valley, but it's not the kind of timber that the timber industry wants (maple and birch and aspen -- good for firewood but useless for construction). What they wanted is old-growth fir, and that's up in the mountains, either the Cascade range or the Coast range, both of which are a long way away from any navigable rivers then or now.

Posted by: Steven Den Beste at May 20, 2011 06:33 PM (+rSRq)

It's true that the Columbia river is one of the great rivers of this continent, but it's not really like the others. When you think of a great river, you probably visualize something like the Mississippi, which is kind of like a huge, long, lake. But the Columbia drops a lot more rapidly than those kinds of rivers, and there used to be several waterfalls on it. In addition to Celilo falls, there was Cascade Falls which was covered by the lake behind Bonneville Dam in the late 1930's. And there were stretches of white water; not exactly waterfalls, but not something you'd want to muck with in a steamship, either.

Even at Portland now, the current is something like 5 knots. And because of that, the Columbia Bar is among the most treacherous waters on the planet for navigation.

One of the many unusual things about the Columbia is that it doesn't meander a lot. It can't, really. Where a river like the Mississippi is running through areas of soil, the Columbia channel runs through rock. It passes through the Cascade mountains, with volcanic cliffs on both sides, and then cuts through the Coast range. Meandering is pretty much impossible. And the channel was seriously scoured out by the Missoula Floods.

Posted by: Steven Den Beste at May 20, 2011 06:50 PM (+rSRq)

46 queries taking 0.0934 seconds, 168 records returned.

Powered by Minx 1.1.6c-pink.