April 26, 2013

I No Longer Need Any More MilHist Books...

...for I have just obtained the final word in Military History titles. My friends, cast your gaze longingly upon the newest, and perhaps final, addition to The Shelf:

If ever proof was needed that good things can come in small packages, Lake Michigan's Aircraft Carriers by Paul M Somers is that proof. Clocking in at 128 pages, over three-quarters of them photographs, LMAC tells the story of the USS Wolverine and USS Sable, the world's only fresh-water paddlewheel aircraft carriers. I first wrote about these two training carriers back in 2010, long before I knew about this valuable work, which was released in 2003. It's actually a little sparse on the actual history, beyond simple numbers, but that's okay. We're not here for the numbers, we're really here for the pictures, many of which I've never seen before, and all in excellent quality.

To be honest, however, I can't recommend that you rush out and purchase this book, because I really doubt that you're as insane as I am. If you are, well heck, go crazy... er... I mean... oh, you know what I mean. In any case, it's a fun little addition to The Shelf, and I'm happy I've gotten it. How many people do YOU know that can say they've got a book on freshwater paddlewheel aircraft carriers in their collection?

If ever proof was needed that good things can come in small packages, Lake Michigan's Aircraft Carriers by Paul M Somers is that proof. Clocking in at 128 pages, over three-quarters of them photographs, LMAC tells the story of the USS Wolverine and USS Sable, the world's only fresh-water paddlewheel aircraft carriers. I first wrote about these two training carriers back in 2010, long before I knew about this valuable work, which was released in 2003. It's actually a little sparse on the actual history, beyond simple numbers, but that's okay. We're not here for the numbers, we're really here for the pictures, many of which I've never seen before, and all in excellent quality.

To be honest, however, I can't recommend that you rush out and purchase this book, because I really doubt that you're as insane as I am. If you are, well heck, go crazy... er... I mean... oh, you know what I mean. In any case, it's a fun little addition to The Shelf, and I'm happy I've gotten it. How many people do YOU know that can say they've got a book on freshwater paddlewheel aircraft carriers in their collection?

Posted by: Wonderduck at

07:32 PM

| Comments (1)

| Add Comment

Post contains 231 words, total size 2 kb.

April 05, 2013

When Aircraft Carriers Flew

Over the years, I've written about all sorts of aircraft carriers. Tiny ones, small ones, big ones, bad ones, even aircraft carriers that were submarines. Today, though, I'm going to talk about what might be the strangest of them all: an aircraft carrier that could fly.

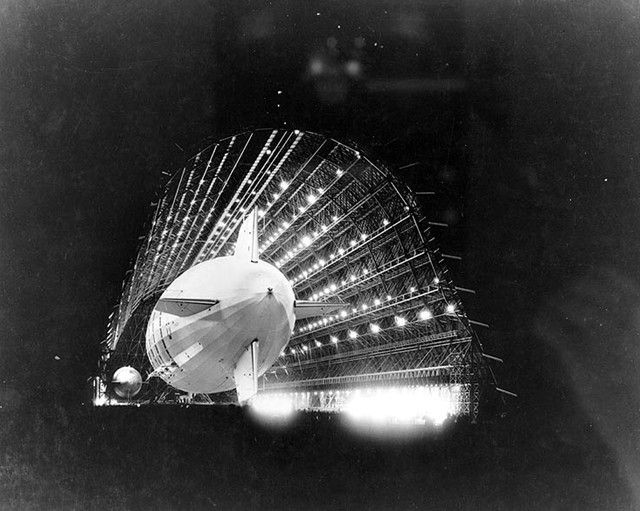

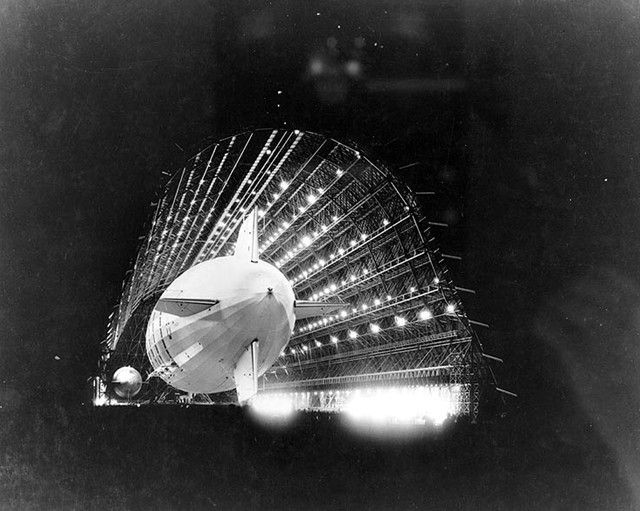

The USS Akron (ZRS-4) and her sister ship, the USS Macon (ZRS-5) were two of the largest things ever to fly, and the largest helium-filled airships ever at 785 feet long. Only the Hindenburg was longer, and only by 20 feet. Despite that immense size, they only weighed 110 tons and could make 72kts at maximum speed. Their role with the US Navy was to be that of reconnaissance. With a range of 12000 miles, more or less, crossed with their speed, they could easily scout ahead of the fleet. However, it was recognized that something that size was hardly invisible and made for one juicy target, even if their helium gasbags meant that they wouldn't go foom the way zeppelins did in WWI. Enter the Sparrowhawk.

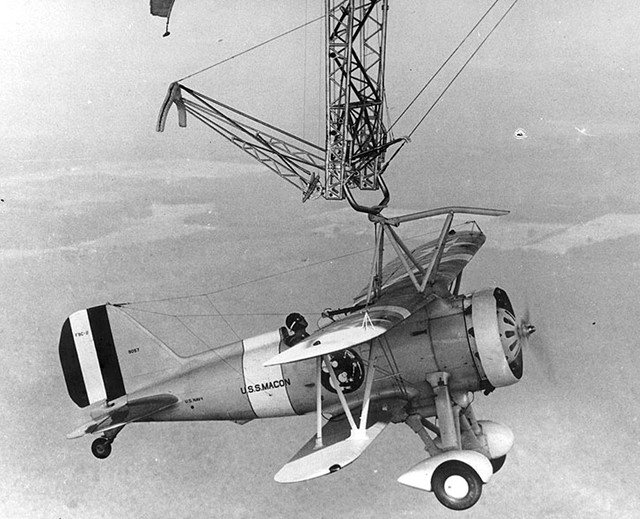

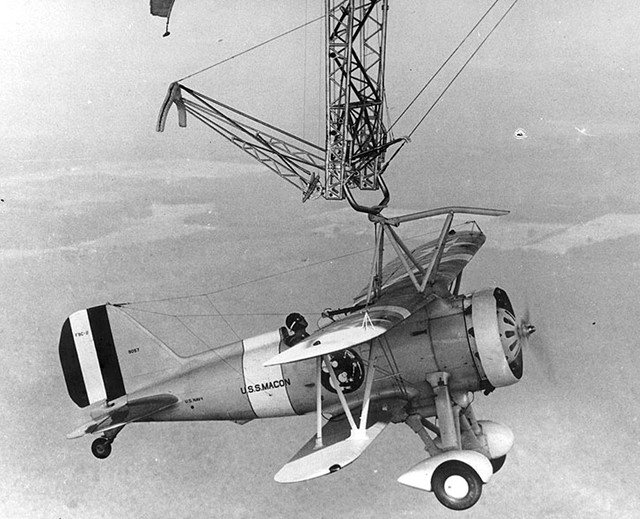

Both the Akron and Macon could carry up to five F9C Sparrowhawk fighters, though four was the norm. These were carried inside the dirigibles, and were launched and recovered via a "trapeze" unit. Simply put, the hook on the top wing would engage the trapeze, which then hauled the plane up into the hangar. To launch, they were lowered via the trapeze, then the hook would be disengaged. The Sparrowhawk would then fall away, in yet another example of why pilots are insane.

The Sparrowhawks were not carried for local defense, though they could certainly perform in that role. Instead, they were to increase the scouting area of the mothership, and allow the Akron and Macon to stay a safe distance from the targets. On the whole, there's no reason why this wouldn't have worked, and test results were generally favorable. There was no terrible difficulty with the trapeze unit, other than the sheer ridiculousness of the concept.

Unfortunately, neither the Akron or the Macon had long careers in the Navy. Dirigibles are, as you can imagine, inherently somewhat fragile. On April 4th, 1933, a mere two years after her launching, Akron was lost when she flew into a storm front over the Atlantic. 73 of her crew of 76 were lost. Two years later, the Macon was struck by a severe gust of wind that carried away her upper tailfin (weakened by a previous accident and insufficiently repaired). She settled gently into the Pacific Ocean, and 74 of her crew survived.

But for a while, they were flying aircraft carriers.

The USS Akron (ZRS-4) and her sister ship, the USS Macon (ZRS-5) were two of the largest things ever to fly, and the largest helium-filled airships ever at 785 feet long. Only the Hindenburg was longer, and only by 20 feet. Despite that immense size, they only weighed 110 tons and could make 72kts at maximum speed. Their role with the US Navy was to be that of reconnaissance. With a range of 12000 miles, more or less, crossed with their speed, they could easily scout ahead of the fleet. However, it was recognized that something that size was hardly invisible and made for one juicy target, even if their helium gasbags meant that they wouldn't go foom the way zeppelins did in WWI. Enter the Sparrowhawk.

Both the Akron and Macon could carry up to five F9C Sparrowhawk fighters, though four was the norm. These were carried inside the dirigibles, and were launched and recovered via a "trapeze" unit. Simply put, the hook on the top wing would engage the trapeze, which then hauled the plane up into the hangar. To launch, they were lowered via the trapeze, then the hook would be disengaged. The Sparrowhawk would then fall away, in yet another example of why pilots are insane.

The Sparrowhawks were not carried for local defense, though they could certainly perform in that role. Instead, they were to increase the scouting area of the mothership, and allow the Akron and Macon to stay a safe distance from the targets. On the whole, there's no reason why this wouldn't have worked, and test results were generally favorable. There was no terrible difficulty with the trapeze unit, other than the sheer ridiculousness of the concept.

Unfortunately, neither the Akron or the Macon had long careers in the Navy. Dirigibles are, as you can imagine, inherently somewhat fragile. On April 4th, 1933, a mere two years after her launching, Akron was lost when she flew into a storm front over the Atlantic. 73 of her crew of 76 were lost. Two years later, the Macon was struck by a severe gust of wind that carried away her upper tailfin (weakened by a previous accident and insufficiently repaired). She settled gently into the Pacific Ocean, and 74 of her crew survived.

But for a while, they were flying aircraft carriers.

Posted by: Wonderduck at

10:17 PM

| Comments (7)

| Add Comment

Post contains 438 words, total size 3 kb.

<< Page 1 of 1 >>

26kb generated in CPU 0.0277, elapsed 0.0866 seconds.

46 queries taking 0.0766 seconds, 169 records returned.

Powered by Minx 1.1.6c-pink.

46 queries taking 0.0766 seconds, 169 records returned.

Powered by Minx 1.1.6c-pink.