January 17, 2011

CV-1

In 1918, the Royal Navy commissioned the world's first ship to be easily recognizable as an aircraft carrier, the HMS Argus. In 1922, the Imperial Japanese Navy commissioned the first ever ship designed and built as an aircraft carrier, the Hosho. In between, the US Navy sent to sea the first of an unbroken line of carriers that led directly to today's nuclear-powered supercarriers.

But on the face of it, the American carrier had a very odd beginning.

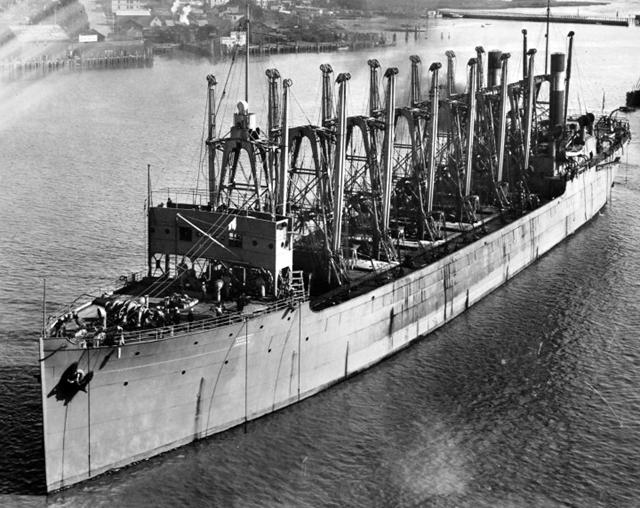

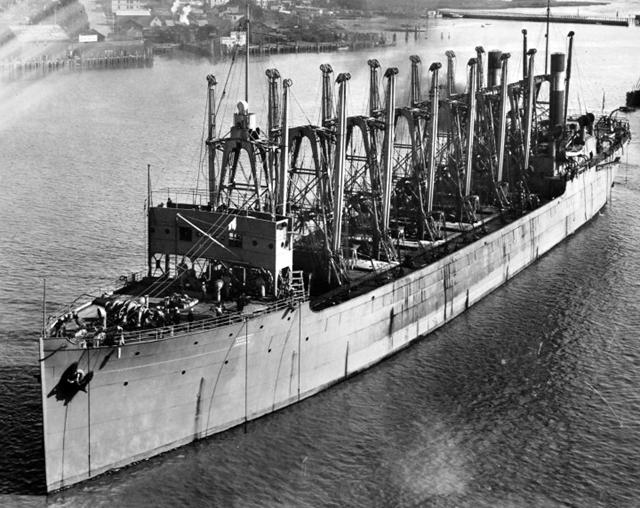

The USS Jupiter (AC-3) joined the fleet in 1913 as the first electric-drive ship in the US Navy. A collier, her job was to provide underway replenishment to the fleet. This task led to her most distinctive feature, the vertical towers, called kingposts, amidships. These were structural supports for coaling booms, which would be lowered when a ship was alongside. Coal would then be sent down the booms to the decks of the receiving vessel.

These kingposts proved to be one of the reasons she was selected to become the basis for the first US aircraft carrier.

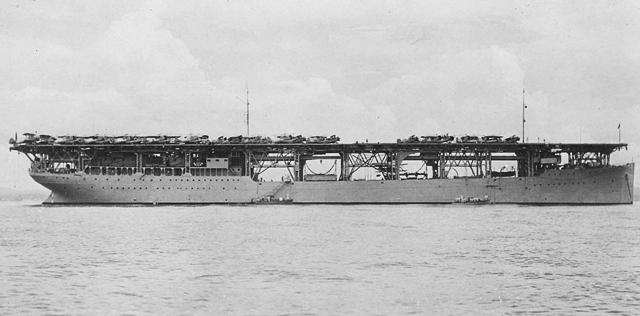

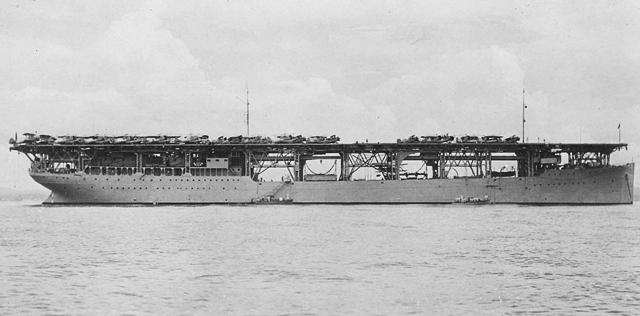

The conversion of the Jupiter to the USS Langley (CV-1) began in 1920 and was completed in 1922. The kingposts were removed, but much of their mounting points to the hull were retained and used to provide anchoring positions for the flight-deck supports. As built, she didn't have a hangar per se. Instead, her planes were stored in the ship's vast hold in a knocked-down condition. They were brought via crane up to an enclosed area at the level of the original main deck, put together, then raised via the single elevator to the flight deck. Most repairs were performed in the hold. The original twin funnel configuration was done away with, replaced by two hinged funnels on the port side aft. The original bridge was kept, underneath the front end of the flight deck. Her odd appearance, with the flight deck looking like it'd been tacked onto a normal ship, lead to the Langley being nicknamed "The Covered Wagon."

Due to her collier origins and keeping her original powerplant, the Langley was never fast enough to actually operate with the battle fleet, maxing out at just over 15kts. At just over 540 feet long, she was short in comparison to what we expect of an aircraft carrier. Even the Hosho, not what you'd consider particularly long, was 10 feet longer than the Langley. Fortunately, aircraft of the time needed little in the way of take-off room. There are photos of planes taking off from her flight deck while the ship is at anchor. Even with a full load of 34 planes on deck, her top speed provided more than enough wind to get the plane farthest forward into the air.

However, her duties were never to be what we'd call a "strike carrier." Instead, the Langley was a true testbed, studying how an aircraft carrier and her embarked air wing should operate. She also provided invaluable service in training every naval aviator on how to fly off of and onto carriers. Her participation in the annual "Fleet Problems" exercises, though limited due to her capabilities, were eye-opening. In fact, she was so successful in these that the Navy actually accelerated the conversions of the Lexington and Saratoga from battlecruisers to carriers. She continued in her role as experimental test-bed for nearly 14 years. In 1936 her long-known limitations, exacerbated by the increasing speed and capabilities of the ships around her, proved to be too much of a liability for her to stay in her role of a carrier. Putting into Mare Island Naval Yard in October 1936, she was decommissioned and was converted again, this time to a seaplane tender.

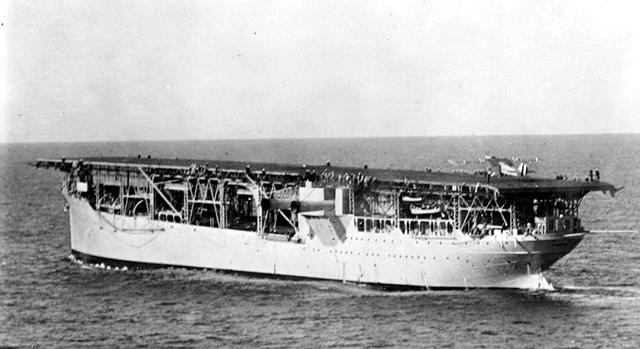

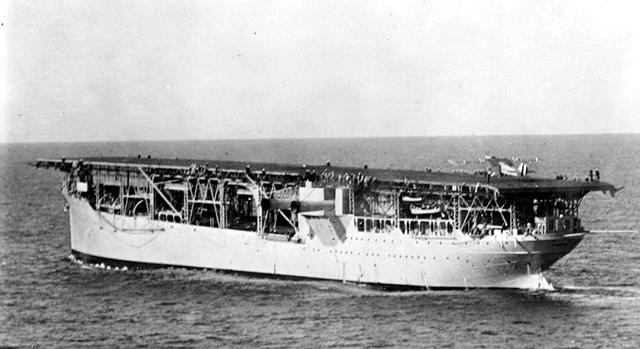

The Langley emerged from Mare Island in 1937 and was recommissioned as AV-3. Other than a six-month stint in the Atlantic in 1939, she spent the rest of her career in the Pacific, based out of Seattle, San Diego, Pearl Harbor and Sitka, Alaska. Her flight deck was cut down, again exposing her original bridge structure.

Planes were no longer stored in the hold, instead being carried on the stub deck in various conditions of assembly depending on the size of the aircraft in question. Some could be craned over the side for flight operations, being assembled on the main deck behind the bridge, but that was no longer her main job. Now she was more of a transport than an actual operator, with repair facilities available if needed.

Planes were no longer stored in the hold, instead being carried on the stub deck in various conditions of assembly depending on the size of the aircraft in question. Some could be craned over the side for flight operations, being assembled on the main deck behind the bridge, but that was no longer her main job. Now she was more of a transport than an actual operator, with repair facilities available if needed.

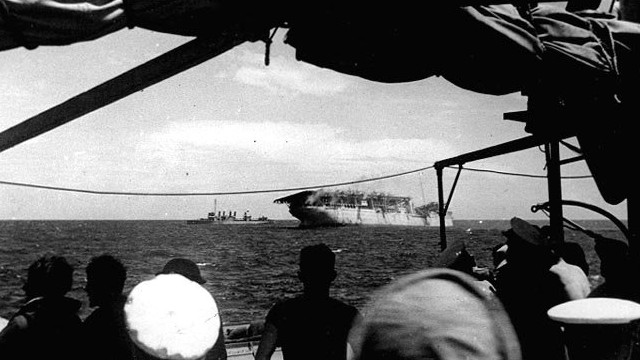

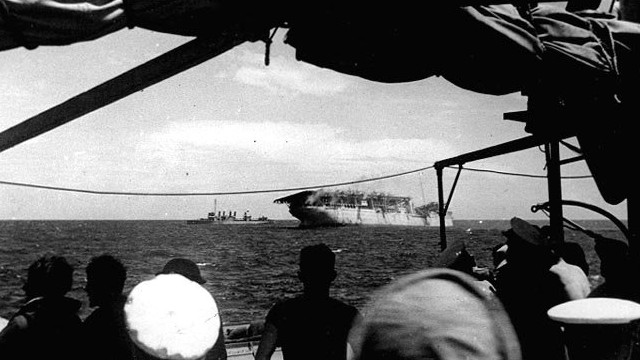

At the beginning of WWII, she was in the Philippines and immediately set sail for Australia to pick up a load of P-40 fighters. She delivered them to Java, then began to return to Fremantle. Spotted about 75 miles south of Java, she was attacked by Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bombers. Caught without air cover and escorted by only two older destroyers, she was quickly smothered by five bomb hits, which killed 16 of her crew.

Her topsides wrecked and on fire, steering disabled, engine room flooded and taking on a 10° list to port, the Langley went dead in the water. Damage control efforts were ineffective, and at 1:32pm on February 27th, 1942, the crew was ordered to abandon ship.

Shortly thereafter, with fears that she could fall into Japanese hands foremost in everybody's mind, her escorting destroyers fired two torpedoes into the side of the Langley, sending her to the bottom and ending her nearly 30 year career.

Without the Langley, much of the US Navy's operational experience in carriers and would have had to have been learned much later than it was. She may not have been good at being a carrier, particularly in comparison to the ships that came later, but it was the experience the Navy gained while operating her that, for example, taught them the value of a large air wing. That right there influenced all of the designs that followed her, leading in turn to the USN carriers becoming the best in the world.

Comments are disabled.

Post is locked.

But on the face of it, the American carrier had a very odd beginning.

The USS Jupiter (AC-3) joined the fleet in 1913 as the first electric-drive ship in the US Navy. A collier, her job was to provide underway replenishment to the fleet. This task led to her most distinctive feature, the vertical towers, called kingposts, amidships. These were structural supports for coaling booms, which would be lowered when a ship was alongside. Coal would then be sent down the booms to the decks of the receiving vessel.

These kingposts proved to be one of the reasons she was selected to become the basis for the first US aircraft carrier.

The conversion of the Jupiter to the USS Langley (CV-1) began in 1920 and was completed in 1922. The kingposts were removed, but much of their mounting points to the hull were retained and used to provide anchoring positions for the flight-deck supports. As built, she didn't have a hangar per se. Instead, her planes were stored in the ship's vast hold in a knocked-down condition. They were brought via crane up to an enclosed area at the level of the original main deck, put together, then raised via the single elevator to the flight deck. Most repairs were performed in the hold. The original twin funnel configuration was done away with, replaced by two hinged funnels on the port side aft. The original bridge was kept, underneath the front end of the flight deck. Her odd appearance, with the flight deck looking like it'd been tacked onto a normal ship, lead to the Langley being nicknamed "The Covered Wagon."

Due to her collier origins and keeping her original powerplant, the Langley was never fast enough to actually operate with the battle fleet, maxing out at just over 15kts. At just over 540 feet long, she was short in comparison to what we expect of an aircraft carrier. Even the Hosho, not what you'd consider particularly long, was 10 feet longer than the Langley. Fortunately, aircraft of the time needed little in the way of take-off room. There are photos of planes taking off from her flight deck while the ship is at anchor. Even with a full load of 34 planes on deck, her top speed provided more than enough wind to get the plane farthest forward into the air.

However, her duties were never to be what we'd call a "strike carrier." Instead, the Langley was a true testbed, studying how an aircraft carrier and her embarked air wing should operate. She also provided invaluable service in training every naval aviator on how to fly off of and onto carriers. Her participation in the annual "Fleet Problems" exercises, though limited due to her capabilities, were eye-opening. In fact, she was so successful in these that the Navy actually accelerated the conversions of the Lexington and Saratoga from battlecruisers to carriers. She continued in her role as experimental test-bed for nearly 14 years. In 1936 her long-known limitations, exacerbated by the increasing speed and capabilities of the ships around her, proved to be too much of a liability for her to stay in her role of a carrier. Putting into Mare Island Naval Yard in October 1936, she was decommissioned and was converted again, this time to a seaplane tender.

The Langley emerged from Mare Island in 1937 and was recommissioned as AV-3. Other than a six-month stint in the Atlantic in 1939, she spent the rest of her career in the Pacific, based out of Seattle, San Diego, Pearl Harbor and Sitka, Alaska. Her flight deck was cut down, again exposing her original bridge structure.

Planes were no longer stored in the hold, instead being carried on the stub deck in various conditions of assembly depending on the size of the aircraft in question. Some could be craned over the side for flight operations, being assembled on the main deck behind the bridge, but that was no longer her main job. Now she was more of a transport than an actual operator, with repair facilities available if needed.

Planes were no longer stored in the hold, instead being carried on the stub deck in various conditions of assembly depending on the size of the aircraft in question. Some could be craned over the side for flight operations, being assembled on the main deck behind the bridge, but that was no longer her main job. Now she was more of a transport than an actual operator, with repair facilities available if needed.

At the beginning of WWII, she was in the Philippines and immediately set sail for Australia to pick up a load of P-40 fighters. She delivered them to Java, then began to return to Fremantle. Spotted about 75 miles south of Java, she was attacked by Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bombers. Caught without air cover and escorted by only two older destroyers, she was quickly smothered by five bomb hits, which killed 16 of her crew.

Her topsides wrecked and on fire, steering disabled, engine room flooded and taking on a 10° list to port, the Langley went dead in the water. Damage control efforts were ineffective, and at 1:32pm on February 27th, 1942, the crew was ordered to abandon ship.

Shortly thereafter, with fears that she could fall into Japanese hands foremost in everybody's mind, her escorting destroyers fired two torpedoes into the side of the Langley, sending her to the bottom and ending her nearly 30 year career.

Without the Langley, much of the US Navy's operational experience in carriers and would have had to have been learned much later than it was. She may not have been good at being a carrier, particularly in comparison to the ships that came later, but it was the experience the Navy gained while operating her that, for example, taught them the value of a large air wing. That right there influenced all of the designs that followed her, leading in turn to the USN carriers becoming the best in the world.

Not too shabby for a hopped-up, funny-looking fleet supply ship.

Posted by: Wonderduck at

12:21 PM

| Comments (5)

| Add Comment

Post contains 1006 words, total size 8 kb.

1

What was the first purpose-built carrier in the world? Was it Lexington (CV-2)? Or some other nation?

Posted by: Steven Den Beste at January 17, 2011 04:50 PM (+rSRq)

2

IJN Hosho was the first ship designed from the keel up as a carrier to be completed. HMS Hermes was probably the first designed, but was completed later.

I should mention that there is some minor debate on this because both ships has convoluted development histories and changed so much in the design process that here is some doubt as to when one can say they were "designed".

First takeoff from a ship was done by the USN, as was the first landing on a ship.

As to the invention of the carrier as an operational concept....That's the UK all the way. They developed the aircraft carrier in WW1 via a series of conversions of fast ferries, liners, battleships being built for export and a crazy uncategorizable THING that made much more sense when they put a flight deck on it.

I should mention that there is some minor debate on this because both ships has convoluted development histories and changed so much in the design process that here is some doubt as to when one can say they were "designed".

First takeoff from a ship was done by the USN, as was the first landing on a ship.

As to the invention of the carrier as an operational concept....That's the UK all the way. They developed the aircraft carrier in WW1 via a series of conversions of fast ferries, liners, battleships being built for export and a crazy uncategorizable THING that made much more sense when they put a flight deck on it.

Posted by: Brickmuppet at January 17, 2011 05:53 PM (EJaOX)

3

Eh, not so much debate as all that. It's generally accepted that the Hermes was the first designed, the Hosho first built. If you use the all-big-gun battleship as the yardstick, then the Hosho is the first purpose-built carrier.

See, the HMS Dreadnought was the first battleship to use an all big gun armament... or, at least, the first to be completed. The Japanese Navy had designed the Satsuma before the British ship, but because there was a gun shortage, the Dreadnought was completed first. From then on, ships with the all-big-gun layout were known as "dreadnoughts" instead of "satsumas."

Occidental bias? Never heard of it...

See, the HMS Dreadnought was the first battleship to use an all big gun armament... or, at least, the first to be completed. The Japanese Navy had designed the Satsuma before the British ship, but because there was a gun shortage, the Dreadnought was completed first. From then on, ships with the all-big-gun layout were known as "dreadnoughts" instead of "satsumas."

Occidental bias? Never heard of it...

Posted by: Wonderduck at January 17, 2011 09:06 PM (W8Men)

4

But I thought that the Dreadnought's claim to fame rested not only on her big guns, but also on her steam turbine engines which gave her great speed. It was the combination of the two in one vessel which rendered all existing warships (including the Satsuma) obsolete.

Posted by: Siergen at January 17, 2011 10:07 PM (Gqqsw)

5

Nope, solely the realm of the guns. The turbines were a bonus, but it was the uniform main battery (of 12" guns) that made the Dreadnought a dreadnought.

Posted by: Wonderduck at January 17, 2011 10:24 PM (W8Men)

26kb generated in CPU 0.0339, elapsed 0.3583 seconds.

46 queries taking 0.3486 seconds, 166 records returned.

Powered by Minx 1.1.6c-pink.

46 queries taking 0.3486 seconds, 166 records returned.

Powered by Minx 1.1.6c-pink.